When I was a pre-teen, I was introduced to the archetype of the college town through various films and television shows. While there are commonalities that show up in most of these types of media, what is often absent is a dignified portrayal of locals living in the communities around these settings. Generally they are treated as an afterthought, with plotlines and character development never addressing the alienation that these people face from the university, as both a large local employer but also as political force with real estate and public safety interests that may conflict with their own. But for those in a official capacity to have to analyze and juggle these different interests, what is a way to respect community and institutional demands?

I went to college in Baltimore, which is a college town without the reputation of being one. It is a rare city to have multiple HBCUs within close distance to multiple private white institutions (PWIs), which both makes for a diverse student body and makes for complex dynamics between campuses and city neighborhoods. Baltimore has been a college town for generations but has seen a marked shift in the last 50 years away from its historic value as a port and manufacturing hub and towards a more “eds and meds” model. At the center of the model is the Johns Hopkins ecosystem. Most prominently at the center of its orbit of institutions is its hospital and medical school, centered about a mile east of downtown. In the city’s downtown proper is the Peabody Institute, its prestigious music school. Two miles further north and outside the city’s central business district is the Homewood campus, site of the undergraduate schools.

For four years, I spent most days during the fall and spring semesters going up and down the many paths and staircases on campus, but also across the neighborhoods of Charles Village and occasionally Hampden. Though the campus dominates this part of the city, various natural and man-made barriers insulate students and faculty from engaging with the blocks around it. Almost two decades ago, students were told to exercise caution in walking into the local neighborhoods, particularly to the east and south. Instead, I and many students without a car, were encouraged to use the JHU van for local trips within a mile and the JHU shuttle bus to go to the other campuses. If I needed to go to one of the other local college campuses, there was another shuttle – one that used traditional yellow school buses – that came hourly.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the multiple layers of buses and shuttles, while convenient and created for the comfort of college students, was one side of a two-tiered transit system that serves the city. In my time in Baltimore, never did I take a city bus even though the campus sits on Charles Street, the main north-south street and divider between the east and west sides and along the route of multiple lines. As I wrote this, I noticed that the city’s bus system has been redesigned into more cohesive grid system. A bus network that was competitive in serving this audience would boost ridership citywide and diminish the existing Hopkins bubbles.

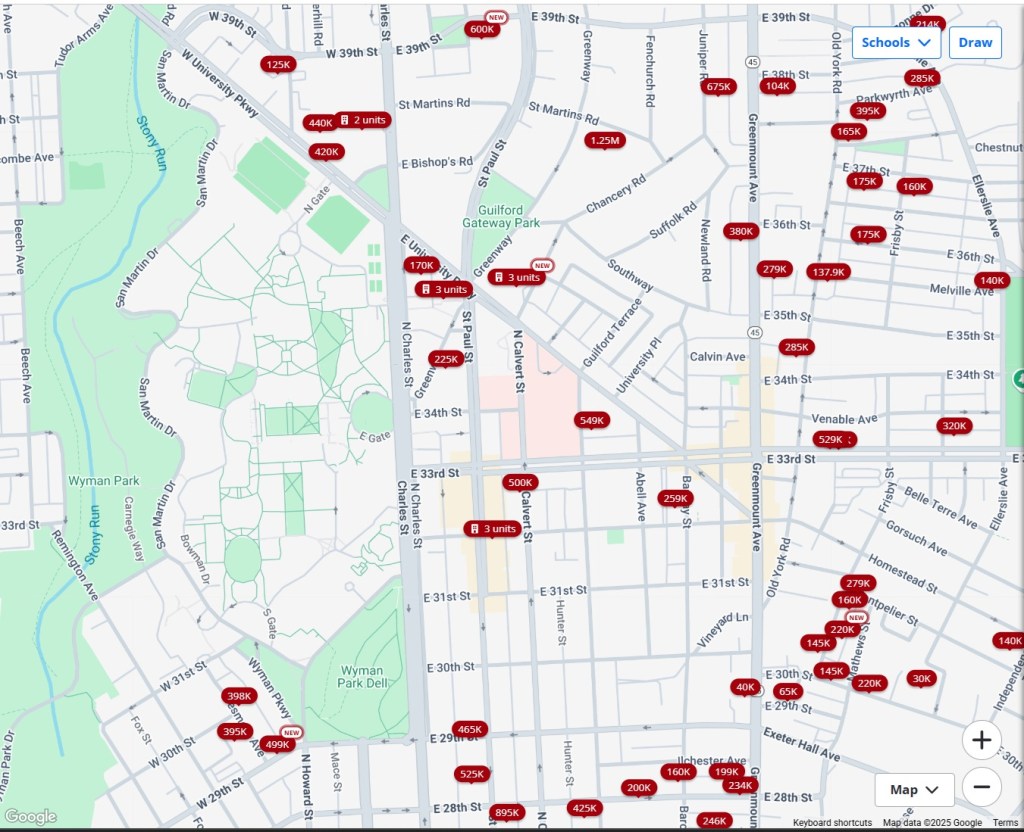

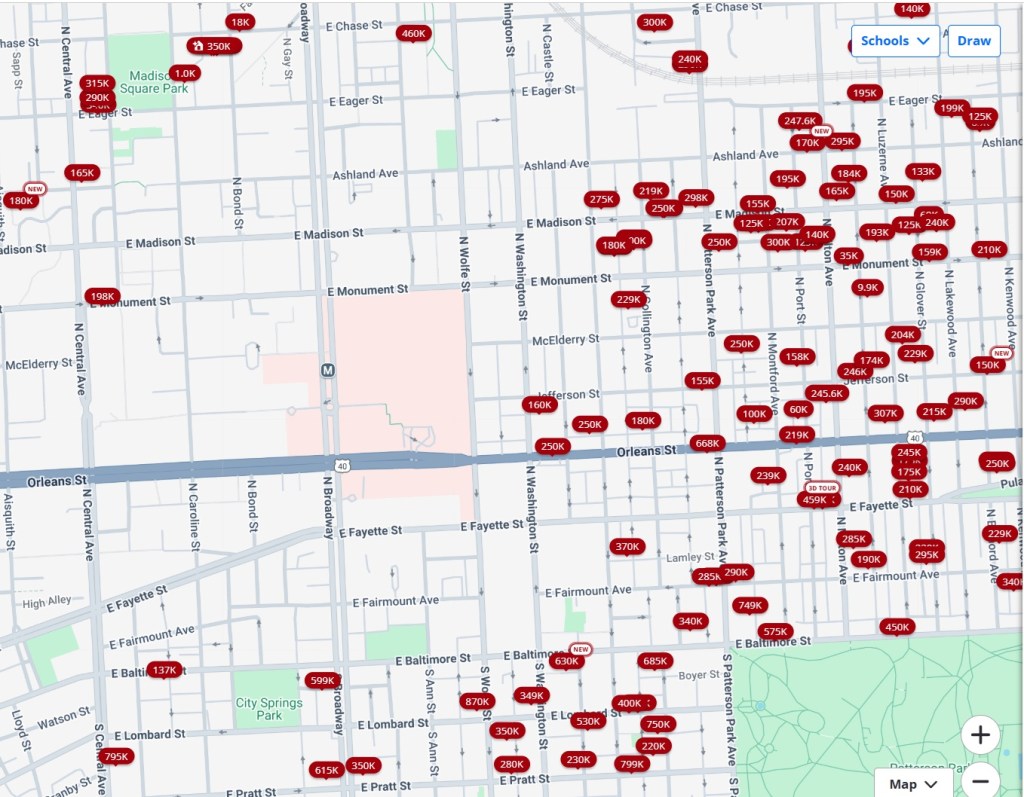

Similarly, housing in college towns is a social good that become bifurcated between college affiliated residents and longtime locals. In the case of Baltimore, there are sharp boundaries around the Johns Hopkins medical and undergraduate campuses and the neighborhoods on their periphery. It is a ‘city of neighborhoods’ where expectations of safety and value shift in a mater of blocks. For reference, you can see a map of Zillow with listings of houses for sale.

As an undergraduate, most of my options off campus were roommate situations. I made due, and so do thousands of other students, but does it have to be that way? I think there are a few different considerations to weigh – I think there is clear demand for more rentals and opportunities for homeownership around the Hopkins bubble. By the Homewood campus, there are a few high rises that almost exclusively serve students but (in my opinion) there could be more. Baltimore isn’t a small city but has large differences in desirability between neighborhoods, described by some as the ‘White L and the Black butterfly’.

While they still can, local leaders must stake a claim where they can and create a clear vision for how their neighborhoods will change and evolve. The Hopkins bubble isn’t going anywhere and while Baltimore still has a relatively poor reputation, it still finds itself in the middle of larger metropolises dealing with their own housing crises. Baltimore has presented itself as a cheaper option for DC commuters for decades now, with mixed results. The two cities, despite their proximity, have two different identities, and that is okay. However, Hopkins (or any other large educuational institution) cannot just be allowed to operate towards its economic interest alone. They certainly have a role in the development of the city into the long term but that place needs to be shaped – both in scope and in place. People chose college towns to settle down in because of both the type of people already there but also the amenities they can access. That requires a university to be open to serving the community at large and not just their student body.

Leave a comment