August marked the 2-year anniversary of the water crisis that plagued the city of Jackson, Mississippi through much of 2022 and a good portion of 2023. I must emphasize that the crisis impacted the city of Jackson, rather than the region, and highlight the many implications of that fact. What should have become a collaboration between municipal and state officials turned into a rather public media battle that displayed many of the general conflicts that mayors of large cities face with the governors of their states, and some of the intricacies of local Black politics all across America, but particularly in the Deep South.

At the center of this crisis lies the less newsworthy but important politics behind infrastructure maintenance and the tensions between the municipal government of Jackson and the state government of Mississippi. Jackson’s City Hall is only a couple blocks away from the Governor’s Mansion and State Capitol but they are worlds apart in the constituencies they seek to serve meaningfully and how they connect to their physical location. The capital city, though the center of governance and economy, is in many ways an island in the state more broadly in multiple respects.

My first glimpses of Jackson came from reading Richard Wright’s memoir Black Boy. Wright’s viewpoint of the city came from someone who moved there as a child and would become increasingly isolated throughout his adolescence before leaving after high school. Even the relatively small and deeply racialized Jackson of the 1920s was a place of relative opportunity for Black residents leaving the state’s rural areas. But Wright’s Jackson was a world away from Eudora Welty’s Jackson. The city would see its population more than double between 1900 and 1910 and double again between 1920 and 1930. While many, Wright included, would leave the American South as part of the Great Migration, many more stayed and landed in large cities like Birmingham, Atlanta and New Orleans.

While Black populations swelled in large cities across the Deep South, the political bases of their respective states remained largely White and rural. In almost all of these states, Black majorities or pluralities would be politically locked out through a complex system of unwritten rules and codified practices that would funnel them from rural isolation to urban concentration in the years before World War II. They would be both squeezed off of land they owned or worked as sharecroppers, to be then boxed into designated slums through racialized zoning laws, reinforced through the practice of redlining as part of the New Deal. The South fought the federal package and relented only with the condition that key pieces, such as Social Security, would exclude Black citizens.

The last century in the United States has seen some of the largest public undertakings in public infrastructure, most notably our interstate system. The highways that now cross the nation blew holes through the heart of many Black communities, though I-20 and I-55 go around downtown and not through it. What it did do instead, was lead a path of white Jacksonians out of the city to nearby suburbs and in the process, create a deep political and personal connection between these highways and their sense of self and freedom. It is not just a simple piece of infrastructure but a key part of their ability to maintain just the level of distance to not feel obligated to address many of the urban issues that plague Jackson, but still able to reap most of the economic benefits of being close to a major city.

Fast forward to the 2010s, where the more clear beginnings of the modern water crisis begin. In 2012, the city was investigated for violations of the Clean Water Act, which included over 2,000 instances of sanitary sewer overflows, times when residential or commercial wastewater was released untreated into local waterways such as the Pearl River. After discussions with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Justice, and Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality, the city paid a $400,000 fine and accepted a consent decree that created a timeline for the city to make sure its wastewater treatment facilities were back in compliance with state and federal water quality laws.

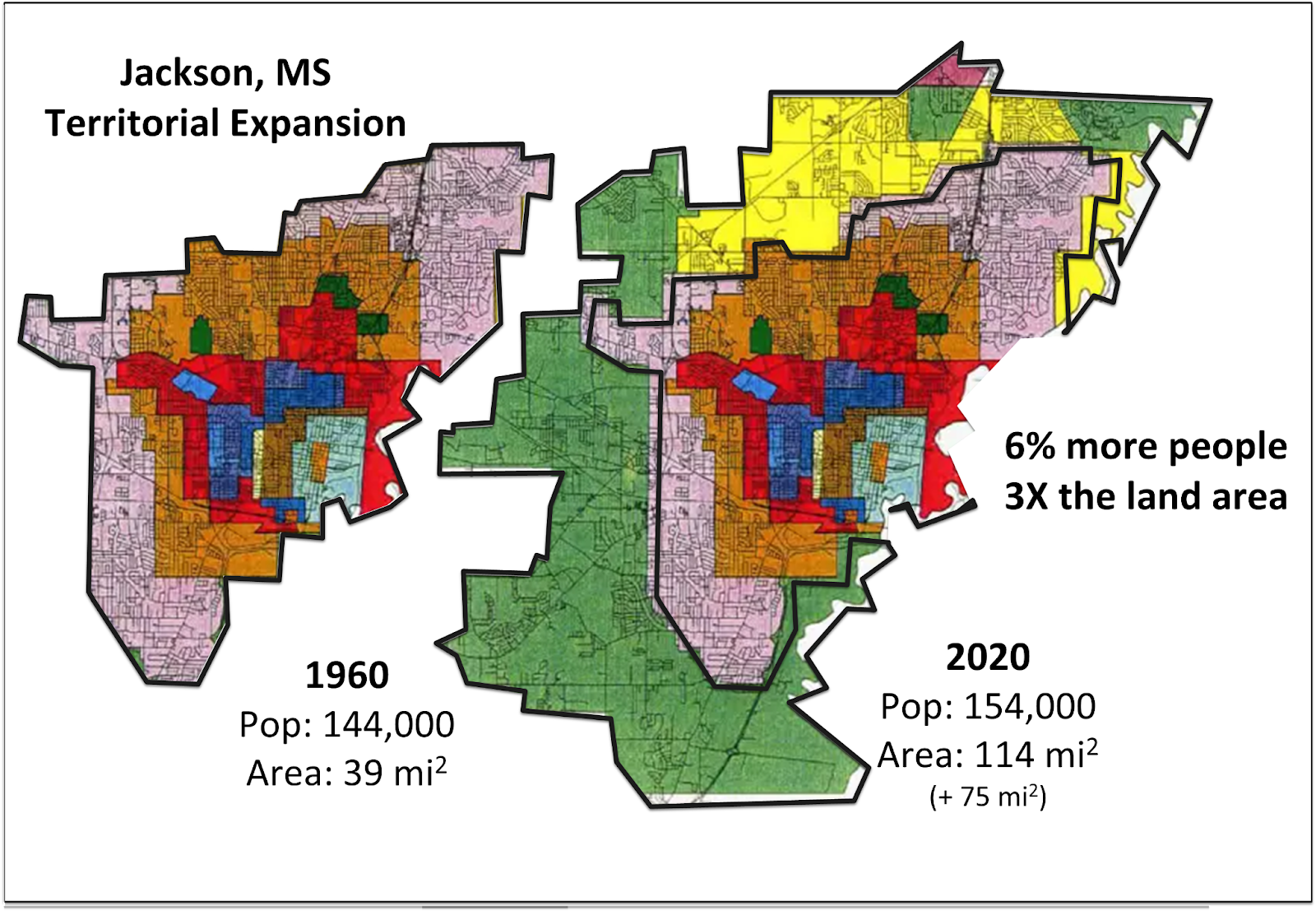

By this time, Jackson was being governed by the late Chokwe Lumumba, a longtime organizer, attorney and former member of the Jackson City Council. He and his son Antar – current mayor of Jackson – have been members of a line of Black mayors for the city going back 25 years, but that hasn’t necessarily meant that Black residents of the city have had any closer relationship to power at the Governor’s Mansion. Jackson’s water issues had been well-known generations ago as white leaders watched as the city grew with concerns about how to expand the system to meet the growth and replace pipes that were showing their age even then. Alas, the city has found itself weathering events of system failure more and more frequently through the 2010s and most prominently a couple years ago. On August 29th, 2022, flooding from the Pearl River and Ross Barnett Reservoir overwhelmed the city’s biggest water treatment plant and caused it to fail, leaving most of the city’s 150,000 residents and those living in nearby suburbs without potable water.

So, what does all of that have to do with highways again? In a country as wealthy as the United States, it is quite easy to take for granted both the amount of infrastructure we use in our daily lives but especially the importance and complexity of their maintenance. Highways are by far the most visible piece of publicly financed infrastructure that Americans see and engage with. People see road work every day and see a value for it in the long-term, even if it slows down their commute in the short-term. Other similarly important systems, like sewers, often are not seen as priorities for government funding and a country, we struggle to nurture the level of expertise needed to maintain them well.A decade after the Flint water crisis, American governments still lack the political will to solve the problem of aging piping systems, and it puts our access to safe drinking water at risk. More than that, both governments and the general public fail to appreciate the scale and cost of what needs to be replaced and the number of cities that will be experiencing these crises will only increase. These challenges won’t just be restricted to cities with stagnant economies but even relatively prosperous cities, as this summer’s water crisis in Atlanta has demonstrated. Let’s learn to exercise some restraint and instead of asking for the highway you use to get another lane for traffic, check the state of your community’s pipes.

Leave a comment